|

|

ENGLISH STONE FORUM |

|

.

|

Home

> Issues > Building stone industry in Britain

1

| 2 | 3&4

| 5 |

6

| 7 | 8

| 9 | 10

| 11

|

|

|

5.

Britain's building stone resources - Sedimentary stones

Sandstones: Sandstone is now the most common building stone used in construction in Britain. Historically sandstones have been quarried for building purposes in almost every area of Britain where they occur at outcrop and they are available from almost every part of the geological column. In general, they are the most durable of our sedimentary building stones, however, they have not all proved to be equally resistant to the effects of modem pollution. Today the number of varieties of sandstone quarried has markedly declined since their heyday from the mid 19th to early 20th centuries. Several areas of Britain which in the past produced considerable volumes of building sandstone, particularly around the developing industrial areas of South Wales-Bristol, the Midlands, the North of England and the Midland Valley of Scotland, now have a much reduced or negligible building sandstone production. The decline in the commercial production of building stones from the red and white Triassic sandstones is particularly marked. Limestones: Limestones have been extensively used in the past for building purposes. Many of Britain's most famous buildings are built of limestones of various types e.g.; the Houses of Parliament (Anston Stone) most of our great cathedrals - St. Pauls (Portland Stone), Llandaff (Dundry and Lias stones), Wells (Doulting Stone), York Minster (Magnesian Limestone from Tadcaster and Huddleston quarries) etc. The softer nature of limestone was particularly important where elaborate decorative carving of the stone was required. As with the sandstone industry in earlier times, most limestone outcrops were worked, if only locally, for building purposes. In a few areas the production of limestone for building stone developed into a major industry and their products were exported throughout Britain and in some cases abroad e.g Bath and Portland stones. Occupying an important niche in some areas, was the quarrying of relatively soft Chalk (e.g Totternhoe and Clunch) lithologies, for elaborately carved decorative work as in the cathedrals of Ely and Exeter. |

Portland stone St Paul's Cathedral, London |

Flints,

ironstones, septaria and tufa: In the absence of suitable sandstones

and limestones, other sedimentary lithologies were often pressed into local

use. Over much of the Upper Cretaceous Chalk outcrop siliceous flints were

commonly quarried or mined for decorative facing stones or rubblestone

walling. The ironstone units of the Lower and Middle Jurassic, which commonly

have variegated rich yellow-brown hues, were widely used in the past for

local buildings. Other unusual building stones include the large calcareous

septarian nodules and tufa (see below).

Igneous stones 'granites': Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries Britain was the worlds leading granite producer. The industry was centred, principally in two areas, the north-east of Scotland, notably around Aberdeen and Peterhead, but also at many smaller granitic outcrops (Anderson 1939), and in south-west England around the large but separate igneous intrusive centres in Devon and Cornwall (Harris 1888). Smaller production centres developed at Shap, Cumbria and at Mountsorrel (granodiorite) in Leicestershire. In more recent times there has been a major contraction of our granite industry. Surviving production is still concentrated in these traditional areas but the number of quarries has been significantly reduced. This is despite the fact that in our new buildings ’granite’ still commonly used in considerable amounts for cladding, however, most of it now comes from overseas sources. |

Higher Shilstone granite Dartmoor Devon |

The

'granite city' of Aberdeen provides a good example of the early importance

of the building stone industry to the local economy and in creating the

character of an area. The most famous of the Aberdeen granites is the coarsely

crystalline silver-grey variety from the Rubislaw Quarries. Most of the

notable buildings in the city are built of this stone and considerable

quantities were exported overseas. The old quarries operated from at least

the 17th century and lie within the present city limits, they ceased operation

in 1971 having supplied stone continuously for almost 400yrs (Donnelly

1974).Its success was based not only on the quality of the stone but also

on its location near the rapidly developing city and, for export purposes,

its proximity to the port for transportation. Also near Aberdeen are the

Kemnay, Sclattie and pink Corrennie quarries. The quarry owners were able

to improve production with new technological innovations. At Kenmay the

first steam cranes and later the Blondin system (an overhead cable lift

for raising stone from the deep quarry flood were developed. Improvements

were also made in the ancillary industries where improved polishing and

cutting technologies were developed. Important granite quarries also operated

around Peterhead (reddish-brown) and Cairngall (grey) both with an extensive

export trade to London and other British cities.

Elsewhere in Scotland other granite quarries include the deep red Ross of Mull, perhaps best be seen outside Scotland in the ostentatious Albert Memorial in London (Robinson 1987), and grey Criffel/Dalbeattie granite from Kircubright. Output from the Scottish quarries increased from about 12,000 tons in 1797 to 260,000 tons by 1939 (Anderson 1961). Granite was produced from several quarries in each of the five separate granite bosses that intrude the Devon and Cornwall peninsular. Production, in its heyday in the 19th century, was centred on the Dartmoor (Hay tor), Bodmin (Cheesewring and De Lank), St Austell (Luxullian), Penryn (Camsew & Penryn) and Penzance areas. In general they can be distinguished from those varieties quarried in Scotland by their coarse often porphyritic nature and the common flow orientation of the feldspars. Though both grey and pink feldspar varieties occur the former tend to dominate. Proximity to the rivers or coast for shipment were again a contributing factor to the national success of the industry in this area. In most of the rock formations of Britain if the stone was hard enough it was invariably used for local building purposes in the past. Many finer grained, intrusive igneous rocks were used in this way such as the dolerite of the Whin Sill in Northumberland. This hard, fine-grained dark coloured rock or whinstone was used in local village houses (e.g. Craster) but because of its intractable nature was more widely exploited as an aggregate. In Exeter and south Devon the local vesicular basalts known as trap were widely used in its ancient buildings including parts of the original fabric of the cathedral. Included by geologists in the igneous rock classification are the serpentinites. These colourful ultrabasic igneous rocks are commonly used for the decorative cladding of shop fronts. Most serpentinites are, however, now imported. Two areas of Britain were known for their production of serpentine, the Lizard area of Cornwall and the Isle of Anglesey in Wales. In Anglesey the serpentine was known as the Mona Marble. |

.jpg)

Welsh slate roof Llanelian Anglesey |

Metamorphic

rocks Slate: Slate is defined by geologists as a fine grained rock

which has a pronounced cleavage Slates were produced by the metamorphism

of pre-existing fine grained rocks, principally mudstones and/or fine grained

tuffaceous (volcaniclastic sediments) in Britain. The slatey cleavage,

which allows the rock to be split into thin sheets along with its impervious

nature are, to the stone industry its most important characteristics. The

cleavage is developed by the reorientation and reprecipitation of micaceous

and platy mineral grains during the high temperatures and pressures inherent

in the metamorphic process and is usually but not always unrelated to original

depositional bedding planes.

This definition of slate excludes the stone products known as 'stone' slates which are naturally fissile limestones and sandstones, widely used for roofing purposes, but which are not metamorphosed in any way. Like the granite industry, Britain's slate industry, which dominated world production in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, has suffered not only from foreign competition but also from an increasing tendency to replace natural slate roofing with man-made clay and concrete tiles. Britain's slate production is still concentrated in its the traditional areas of North Wales, the Lake District and Devon and Cornwall. However, the industry once also thrived in Scotland (Easdale (Tucker 1976), Ballachullish (Fairweather 1974), Foudland (Richey & Anderson 1945?), West Wales (Ri chards 1997) and Leicestershire (Swithland) but has now virtually died out in these areas. This decline cannot be attributed in any way to the quality of the slates produced or to a lack of reserves but probably to economics, and the decline in skilled slaters able to lay slates efficiently in the traditional way. There is also an apparent indifference which architects and planners now seem to have over specifying British slates for new build projects, rarely do you see natural slates used in modern housing developments despite their proven durability. |

| Marble:

To the geologist a true marble is a metamorphosed limestone i.e a completely

recrystallized sedimentary limestone. In Britain, by this definition, there

are few true marbles which have been exploited for building or decorative

stone. To the stone industry, however, the term marble can include any

sedimentary limestone hard enough to be cut and polished.

Britain's 'marble' industry was based largely on the exploitation of limestones which, because of their hardness and fossiliferous structure, could be cut and polished to produce an attractive 'marble-like' finish. True metamorphosed marbles, with few exceptions, if needed had to be imported from Europe and elsewhere and marble imports into Britain for decorative purposes date back as far as Roman times. |

|

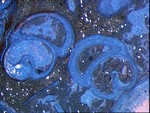

Thin section of Purbeck 'marble' |

Probably

the best example of the industry usage of the term marble (polished limestone)

in Britain is the well known Purbeck Marble of Dorset. These hard, thin,

fossiliferous freshwater limestone beds have been exploited as a decorative

stone since Roman times. The Purbeck Marble is not a metamorphosed limestone

as is evident from the preservation, without deformation or alteration

of the thousands of small freshwater gastropod shells that make up much

of the rock. The Sussex Marble, from the Lower Cretaceous of the Weald,

is similar in character to the Purbeck and often mistaken for it by the

untutored eye. Other sedimentary 'marbles' which achieved at least local

fame include many limestones from the Carboniferous rocks of Britain, such

as Frosterley (a black limestone rich in white coral fragments), Nidderdale,

Dent and Egglestone (black crinoidal limestones) and several colourful

limestones from Derbyshire (Ashford Black, Bird's Eye, Duke's Red etc).

The so-called Draycott Marble from Somerset is a polished coarse grained

breccia composed of numerous reworked fragments of Carboniferous limestone.

The only true metamorphosed limestone marbles quarried in Britain were worked in western Scotland in Tiree, Skye etc, some achieved short-lived commercial success such as the serpentinous green and white streaked variety from the Isle of Iona quarried from the Pre-Cambrian outcrops (Dimes 1990; Viner 1992). A recent revival is the variegated serpentinous marble from the Ledmore Quarries in Sutherland. In the Pre-Cambrian Mona Complex of north west Anglesey the once famous Mona Marble ('leek' green to dark green and purple serpentinite) was quarried on a small commercial scale for decorative use (Hull 1872). |

| 1 | 2 | 3&4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| . |

|